Since leaving grad school, one of the biggest challenges has been coping with the loss of access to databases. I could write an ode to JSTOR and EBSCO about how much I miss having unlimited access to journals and images. But like the famed poets of the Counting Crows said, you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone…

Then along came the pandemic and all the sudden JSTOR announced free access to hundreds of articles through the year!

While it doesn’t seem like one can access everything, simply having a greater number of clicks on the site for free has been a game changer for public access. I encourage anyone interested to create a free account and begin by browsing their collections.

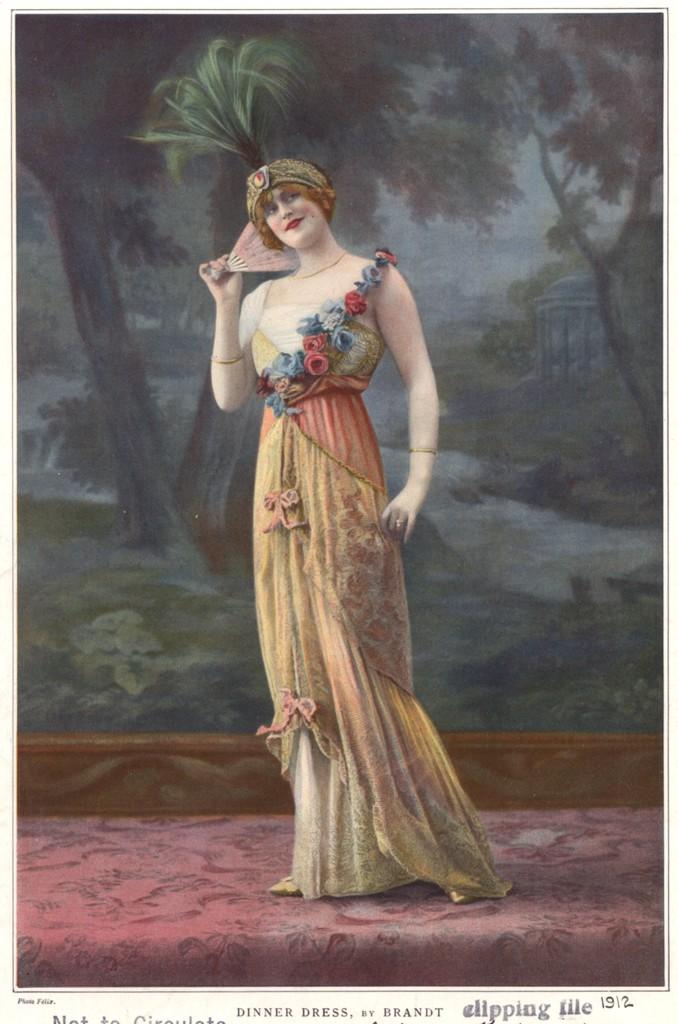

One collection that I found interesting is the “Edwardian Fashion Plates.” With images from some of the most high-end magazines dated 1910 to 1914, these images highlight the gold standard of dress on the eve of the most destructive war the world had known up to that point.

The Edwardian Era refers to the period from 1901 to 1914 and coincides with the reign of the British monarch, Edward VII. It might seem strange to refer to a period of European history after the monarch from a single nation–it’s odder still when that monarch only lived until 1910–but while different countries may have different names for the decade preceding WWI, the “Edwardian Era” remains the most fitting here.

In many ways, the prints featured here highlight the cosmopolitan nature of the age. Most of the images in the collection were published in Les Modes, a French fashion periodical. While based in Paris, the magazine also distributed to London, Berlin, and New York.

It took a while for fashion magazines to take their modern form. In the decades before the turn of the century, the Industrial Revolution created a new kind of worker that relied on a more regulated schedule. It also increased the accessibility to mass produced products and means of selling these goods.

Quickly marketers realized they could increase sales by targeting specific demographics. Men’s and women’s magazines flew off the shelves beginning in the 1880s. Around the turn of the century, the first major department stores like Selfridges opened in London (1909).

In the 1890’s, the first fashion models as we would understand them appeared in print. Vogue launched in New York in 1893 with a British version following 23 years later. Popular modeling in the fashion industry began with the Gibson Girl–a personification of the “ideal” woman as illustrated by Charles Dana Gibson. Ten years later and with cheaper photo printing techniques, women like Evelyn Nesbit became the first photo shoot celebrity models.

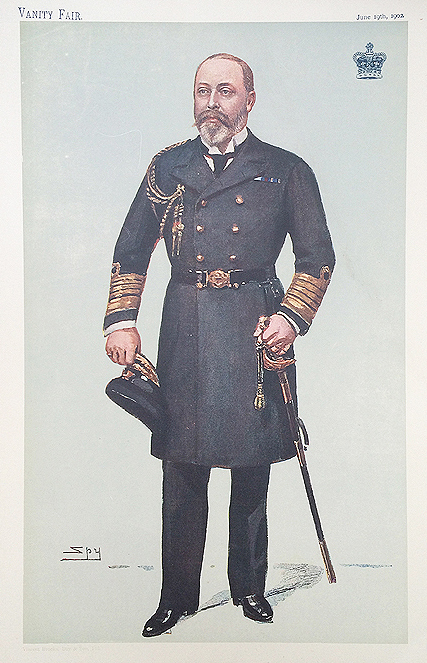

These types of images often found their way into magazines like Vanity Fair, which had been printed in Britain since the 1860s. Vanity Fair (unrelated to today’s US version revived in 1983) didn’t specifically target women, but countless magazines soon did. The ability to market a specific mass-produced good by utilizing its photo in a magazine became monumentally influential to later publications that took more direct sales approaches like the Sears, Roebuck & Company Catalogue beginning in the 1920s.

While this new consumer culture of the Edwardian Era may make surprisingly frivolous, it fit well under the umbrella of the man who lent his name to the age.

Edward VII was the son and heir of Queen Victoria (of the “Victorian Era” and heiress of the “Georgian Era/Regency”). Because of Victoria had nine children and many more grandchildren who married into royalty across Europe, Edward was well connected. He was directly related to the monarchs of Germany, Russia, and several other regions.

Edward’s son and successor George V would eventually align himself with one cousin, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, against another cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, in World War I (1914-1918).

We like to think of Victorians as restrained individuals who lived under strict rules imposed by a puritanical society, but this can’t be further from the truth for many living in the age. Edward was so well known for his proclivity for socializing that upon ascending to the throne, some commentators called him “Edward the Caresser” (in reference to the highly un-Edwardian and pious Medieval monarch Edward the Confessor).

But Edward and his wife, Queen Alexandra, also brought something to the British monarchy that had been lacking for decades–flair. Edward VII and Queen Alexandra became fashion icons of the aristocratic classes of Europe. While his parents Albert and Victoria had often worn plain attire, Edward loved luxurious clothing. After decades in which Queen Victoria wore only black mourning dress, Edward’s sense of style was a breath of fresh air.

Rather than dismissing his fashion as gaudiness, the public turned Edward into someone that even the unlikeliest of people tried to emulate. Baron Hermann von Eckardstein, the German ambassador in London at a time of increasingly strained Anglo-German relations, was a notorious Anglophile who styled himself after Edward and loved to be seen about the London clubs.

Edward was a monarch who sought to increase Britain’s involvement in the affairs of Europe. In his early years as a dashing Prince of Wales, he was featured regularly in Vanity Fair and The World. As a monarch he understood the power of the press and used the same international connections to earn the nickname “Peacemaker of Europe.”

Although that peace didn’t last long beyond his death in 1910, Edward VII’s full story is for another post. Still, it’s clear that the decades around the turn of the century were remarkably cosmopolitan.

Looking at pictures like these from just over a century ago, we can see a lot of the same ideas of how to display and sell fashion as we see now. They also tell a story of an age that feels distant yet remarkably close. While I don’t think anyone’s clamoring to hop into some of these clothes, you have to admit that the Edwardians had style and knew how to sell it!

JSTOR’s free trial highlights the power of public access. With so many students, educators, and history fans working from home, it’s more important than ever to give people the tools they need to engage with history. While I can’t wait until I’m able to return to archives and museums in person, I’m also excited to see how people’s ingenuity will continue to shape historical interaction.

Citations:

- Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2013).

- Jane Ridley, The Heir Apparent: A Life of Edward VII, The Playboy Prince, (New York: Random House, 2013).

- W. Hold-White, The People’s King: a short life of Edward VII (London: Ballantyne & Co. Limited, 1910).

Image citations:

- Brandt (fashion Designer). Dinner Dress. Accessed September 23, 2020. doi:10.2307/community.22291350.

- Doeuillet, Georges (fashion Designer). Afternoon Dress. Accessed September 23, 2020. doi:10.2307/community.22291378.

- “His Majesty the King,” Vanity Fair, June 19, 1902.

Leave a Reply