For as long as humans have been around, we have been grooving to beats and singing songs. But music can often be used as a tool to motivate and galvanize people to feel certain emotions or do certain things. For most armies of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, drums and pipes served dual purposes. First and foremost they were used to issue orders and organize forces on the field as one beat would signal some action while another would mean something else. But their second purpose was to motivate, steady, and shore up the men whether on the battlefield, during a march, or in camp. You know how you like to listen to the latest Top 40 Trash on the radio while on road trips? Well the soldiers back then liked to have a beat to march to on long walks and would even sing along sometimes if they were allowed. Then later in camps you might hear soldiers singing more solemn songs around a camp fire that remind them of home and loved ones. Clearly, music was part of military culture for a long time.

Yet songs were different back then. Without radio around to repeat a wide variety of music or records so you could listen as many times as you wanted, it could be difficult to learn and memorize a new song. That is why often times people simply wrote new lyrics to tunes they were already familiar with. In fact, America’s national anthem was initially a poem that was later set to the tune of a popular English drinking song!

The American Civil War was no exception and during its four years music was used to motivate men to enlist, steady them before a fight, or help people mourn the loss of friends and family. Yet there is perhaps one particular regiment that was well known as the most sung-about during the war–the 69th New York Infantry Regiment.

Made up predominantly of Irish-Americans, the “Fighting 69th” suffered the third most casualties of any brigade in the Civil War. Still, it should be no surprise that the men of this force brought with them many of the traditional songs and tunes of Ireland with them into the American Army and changed them to fit a new U.S. flavor. One song they commonly sang was “We’ll Fight for Uncle Sam.”

This song was set to the tune of “Whiskey in the Jar,” which is one of the oldest Irish folk songs still commonly sang as it dates back to the 17th century. Side note: if you haven’t listened to it yet, you are doing yourself a disservice so check out the version that is the best in my opinion…

It’s catchy, right???

Anyway, it wasn’t long after the rebels opened fire in Charleston and Lincoln mobilized the North in April of 1861 that Irish soldiers changed the lyrics and renamed the song, “We’ll Fight for Uncle Sam.” Here is a link to a really neat image of the original lyrics to the song, courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum:

We’ll Fight for Uncle Sam Lyrics

I am a modern hero: me name is Paddy Kearney;

Not long ago, I landed from the bogs of sweet Killarney;

I used to cry out: SOAP FAT! because that was my trade, sir,

Till I ‘listed for a Soldier-boy with Corcoran’s brigade, sir.Chorus:

For to fight for Uncle Sam;

He’ll lead us on to glory, O! He’ll lead us on to glory, O!

To save the Stripes and Stars.Ora, once in regimentals, my mind it did bewilder.

I bid good-bye to Biddy dear, and all the darling childher;

Whoo! says I, the Irish Volunteer, the divil a one afraid is,

Because we’ve got the soldier bold, McClellan, for to lead us.Chorus:

For to fight for Uncle Sam, &c.We soon got into battle: we made a charge of bay’nets:

The Rebel blackguards soon gave way: they fell as thick as paynuts.

Och hone! the slaughter that we made, by-god, it was delighting!

For, the Irish lads in action are the divil’s boys for fighting.Chorus:

They’ll fight for Uncle Sam, &c.Och, sure, we never will give in, in any sort of manner,

Until the South comes back again, beneath the Starry-Banner;

And if John Bull should interfere, he’d suffer for it truly;

For, soon the Irish Volunteers would give him Ballyhooly.Chorus:

Oh! they’ll fight for Uncle Sam, &c.And! now, before I end my song, this free advice I’ll tender:

We soon will use the Rebels up and make them all surrender,

And, once again, the Stars and Stripes will to the breeze be swellin’,

If Uncle Abe will give us back our darling boy McClellan.Chorus:

Oh! we’ll follow Little Mac, &c.

Now there are some interesting segments of this song that I want to point out and elaborate on…

I used to cry out: SOAP FAT! because that was my trade, sir,

Till I ‘listed for a Soldier-boy with Corcoran’s brigade, sir.

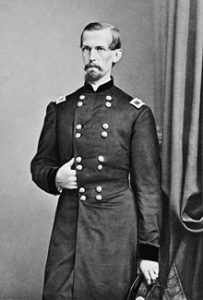

“Cocoran’s brigade,” refers to Michael Corcoran, an Irish-born general who repeatedly lead the 69th into battle up until his death in 1863. Corcoran was a very interesting figure and a devout patriot of both Ireland and the U.S.. In 1860, when Edward, Prince of Wales toured America, Corcoran was supposed to lead the 69th on parade through the streets of New York in honor of the visit from Britain’s playboy heir. However, for centuries relations between Britain and Ireland had been tense to say the least and Corcoran refused to lead his men before the prince. For this he was removed from command and awaiting his court martial when the Civil War broke out. He was only spared punishment because of his ability to galvanize Irishmen to the military.

Whoo! says I, the Irish Volunteer, the divil a one afraid is,

Because we’ve got the soldier bold, McClellan, for to lead us.

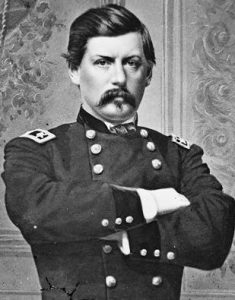

George McClellan is one of the more complicated figures of the Civil War. Put in charge of the Army of the Potomac after Gen. Winfield Scott was removed due to losing First Bull Run, McClellan instantly became a celebrity in the eyes of his troops. They affectionately referred to him as “Little Mac” as you see in the last chorus. McClellan instilled fierce loyalty in his men but equally fierce opposition from his higher-ups. Lincoln quickly grew tired of the general because, although he was spectacular in training troops, he lacked the determined doggedness to provide the pressure on Confederate forces Lincoln sought. After he failed to pursue rebel forces following Antietam in September, 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan from command. Little Mac returned to the public sphere as a Democratic nominee for the 1864 presidential election. As many of the Irish soldiers left the army mid-way through the war and many Irish-Americans rallied as a mob during the New York City Draft Riots, it is unsurprising that Irish troops felt a loyalty to McClellan.

And, once again, the Stars and Stripes will to the breeze be swellin’,

If Uncle Abe will give us back our darling boy McClellan.

The army’s loyalty to McClellan clearly was unparalleled and for the Irish troops it was perhaps even unmatched by loyalty to the nation. Not only do they beg Lincoln to reinstate McClellan to authority, the final chorus changes “We’ll fight for Uncle Sam” to “We’ll fight for Little Mac.” The army’s loyalty would be put to the test in the election yet in the end the soldiers overwhelmingly voted for Lincoln. This election revealed a few different factors. First it showed the importance of the Emancipation Proclamation and military gains such as the capture of Atlanta by Sherman just before the election. Although the Irish (by large) cared little for the affairs of African Americans or their freedom, as Union soldiers moved throughout the South and saw the horrors of slavery first hand they came to appreciate what Lincoln and his government sought to achieve in emancipation. But the 1864 election results also hints at the importance of the soldier (and eventually veteran) voting bloc. This would manifest itself in the Grand Army of the Republic. The G.A.R. was made up of Union veterans and comprised the largest lobbying group of the late 1800s. Although this song hardly refers to voting or emancipation, traces of a political nature can be found if you read carefully enough.

And if John Bull should interfere, he’d suffer for it truly;

For, soon the Irish Volunteers would give him Ballyhooly.

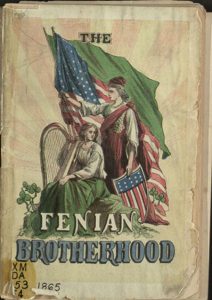

In my opinion this is the most interesting and important part of the song. John Bull is to England what Uncle Sam is to America and back in the 19th century his image was used everywhere to represent the empire. As stated before, tensions between the English and Irish had been rising for centuries and would eventually come to a boiling point with the 1916 Easter Rising. But in the half-century before the Rising, the Fenian Brotherhood was formed. The Fenians were basically Irishmen living in America who vehemently supported a free Ireland and sought to return to their homeland. For many, the American Civil War was an opportunity to learn military tactics and gain valuable combat experience with which they could return to fight off the English forces. Thus the warning to John Bull was double-sided.

On one hand it was a warning that Great Britain should stay out of the Civil War. Many in the North feared Britain would side with the rebellious states and either lend major support or even send troops to assist them. Thus men like Sec. of State, William Seward did everything in their power to prevent this from happening and maintain Europe’s neutrality. Yet on the other hand it was a forewarning of things to come. There is somewhat of a sense that these men want England to interfere just so they could fight some English. Furthermore, they warn that “soon the Irish Volunteers would give him Ballyhooly.” I don’t know what Ballyhooly is but I would not want to be on the business end of it!

In conclusion, I hope you can get a taste for the role of music in wartime. It can be used to motivate troops toward that final push, console them after the battle, or even advocate for a political movement occurring across an ocean. “We’ll Fight for Uncle Sam” was just a number of songs made popular by Irish soldiers and the armies in general so I encourage you to do some YouTube searching for others. Hearing the music played is one of the best ways to achieve a sliver of empathetic connection to the past and it can be one of the most lighthearted aspects of history. Even when one knows of the horrors of the Civil War, the nightmares of those involved, and the atrocities occurring in Ireland at the time, it is difficult not to smile just a bit at the pleasant beat and tone.

Just see for yourself:

Leave a Reply