It’s safe to say that the Civil War isn’t known as a particularly peaceful conflict with little bloodshed. Furthermore, mention of the words “Civil War hospital” brings to mind images of blood-soaked doctors moving from soldier to soldier and chopping off wounded limbs with reckless abandon. The soldiers themselves cry out in agony until infection caused by the use of an unwashed saw kills them an hour later.

But the gory mental images of arms and legs sitting outside medical tents don’t show the full picture. Historians are taking great strides to use the full body (sorry) of evidence to show how the Civil War hospital experience was much more nuanced. What’s even more interesting and misunderstood is the fact that women played a vital role in Civil War medicine.

For much of the early 19th century, medicine looked like it did in the 18th century. Male doctors traveled to the sick or wounded and treated them at their own homes. They used fun tools like leeches and techniques like bleeding.

The mid-19th century saw a major step forward in medicine thanks in large part to women! During the Crimean War (1853-1856) Florence Nightingale helped revolutionize nursing and its role in military medicine. The Englishwoman’s 1860 book, Notes on Nursing, was based on her experiences and soon crossed the Atlantic.

The U.S. government quickly picked up these lessons–largely thanks to another woman, Dorothea Dix. Initially, women weren’t welcome at military hospitals and nursing duties were handled by convalescing soldiers who were too weak to return to their units. Dix was efficient, organized, and so strict that she earned the nickname “Dragon” Dix!

Nurses serving under Dix were required to:

- Be between 35 to 50 years old

- Be healthy

- Be matronly, educated, and have habits of sobriety, neatness, and industry

- Dress in only grey, black, or brown and without any ornamentation like jewelry

- Present certificates of qualification and good character

- Have previously had the measles

Clearly Dix ran a tight ship, but these rules were there for a reason. Dix wanted to discourage any potential hospital romances and make sure her teams were always focused solely on the task at hand. Female nurses drew on traditional societal roles of running households and caring for families, but their actions also led to increased esteem for nurses as an entire profession.

The professionalization of nursing simultaneously occurred with the modernization of the hospital system. For much of the early 19th century, wounded men were left to fend for themselves unless carried off by a comrade. By mid century, the very first Ambulance Corps was established and a system of triage for casualties was set.

The novel triage system was a way to efficiently get wounded soldiers to where they needed to be for each stage of their recovery and looked largely like this:

- Field Dressing Station – located on or near the battlefield. Medical professionals would apply initial treatment and dressing.

- Field Hospital – near the battlefield and usually in structures like homes or barns. Emergency surgery would be conducted here if necessary.

- Large Hospital – further away from the battlefield, these hospitals provided long term treatment and convalescing. [1]

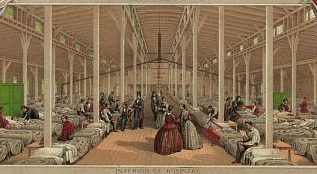

The thought of a Civil War hospital might muster images of smelly, cramped, and dingy buildings more akin to a torture chamber than our modern hospitals. But in reality military hospitals saw major innovations to improve the health and experience of their patients. In many ways, this was helped by the U.S. Sanitary Commission.

Founded in 1861, the Sanitary Commission coordinated thousands of volunteers who raised millions in donations and medical supplies. Although administered by men, women comprised the majority of volunteers. On the ground, the Sanitary Commission sent inspectors to monitor the cleanliness of latrines, water supplies, and cooking facilities.

The Commission also did things like set requirements on how hospitals should be structured. Rows of open windows were installed toward the tops of vaulted roofs. These allowed for ventilation of unpleasant smells, temperature moderation, and plenty of bright light to flood the hospital.

Inside the hospitals, soldiers were able to convalesce in relative comfort. Soldiers rarely had to “bite the bullet” during surgeries. In fact, anesthesia was used in about 95% of all surgeries!

Chloroform and ether were already well known and used widely by the mid century. While occasionally not available for Confederate forces due to the effective Union blockade, the vast majority of amputations and other surgeries occurred under a carefully administered anesthetic.

There are a lot of misconceptions about Civil War medicine, hospitals, and the role of women during the conflict. For many, there’s still the image of soldiers crying out in agony, taking a swig of whiskey to numb the pain, and then biting the bullet as their arm is hacked off by quack doctor. While infections killed soldiers often, medicine wasn’t quite as barbarous as many think.

Even Abraham Lincoln recognized how important women were to the war effort as a whole. In 1864 at the Sanitation Commission Fair, Lincoln stated, “If all that has been said by orators and poets since the creation of the world in praise of women applied to the women of America, it would not do them justice for their conduct during this war. I will close by saying this, God bless the women of America!”

NOTES:

- “Major Jonathan Letterman: Father of Modern Battlefield Medicine,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/jonathan-letterman

- Featured image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Citizens volunteer hospital corner of Broad St. & Washington Avenue, Philadelphia / des. & lith. by J.Queen ; P.S. Duval & Son Lith. Phila. Pennsylvania Philadelphia United States, 1862. https://www.loc.gov/item/98519871/.

Leave a Reply